No matter the side of the dependency injection debate fence you fall, you've probably worked with some .NET code that had some form of object composition through DI at some point, or another. Heck, with libraries in Autofac and .NET Core's dependency injection extension namespace, DI and service container registration is a breeze with all the heavy lifting done virtually for us.

If you've been reading along for the past several posts, you're wondering why I'm not writing about Blazor. Don't get

me wrong, I've got quite a few ideas I'd like to get out on paper here as we venture off deeper into Blazor-land. I

wanted to take a break from the Blazor-scape for a while and write a bit on a topic I've been quite curious about for

some time now. Admittedly, I've fallen victim to the mindset of defaulting most of my .NET Core services lifetimes to

the good ole fashioned .AddTransient() simply because I figured when in doubt, you can't go wrong with the transient

lifetime.

But then I started thinking to myself: "self, do you really understand the difference between service lifetimes?" While I thought I had a clear understanding of the basics going just off the docs, I really wanted to make sure I understood why I was choosing the lifetimes I was for my services. Not only that, I wanted to understand what different types of application scenarios called for particular lifetimes.

Disclaimer: I'm not an Autofac expert, so I'll just be covering services within the scope (no pun intended) of

Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjectionfor the remainder of this post

If you're not familiar with the differing service lifetimes one can choose from when registering a service in a .NET Core application, the team at Microsoft has provided us with three varieties: transient, scoped, and singleton service lifetimes. Before we breakdown each service lifetime and write a bit of code to help us better understand the difference in these service types, let's talk about why we might want to use service registration in an application.

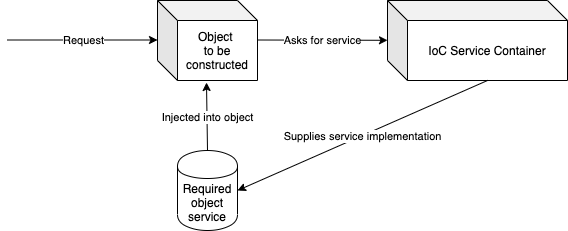

Dependency Injection and Inversion of Control

Now, I like to preface often that I am in no way, shape, or form an expert in the field of software engineering. I write

the blog posts, for the most part, to help me better understand the .NET ecosystem and the tools I use on a daily basis.

So, before I go down the rabbit hole of service lifetimes, it might be best if we understand why we register services in

the first place using something like .NET Core's ServiceCollection type from

the Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection namespace. I like to think of this service container implementation in

the following manner:

Breaking it down, starting from an incoming application request:

- Request comes in ultimately requiring the construction of an object to do some sort of application processing

- The object in question requires another service object to be composed correctly

- Since we've registered that required service in the IoC container, the request object will ask for the service object to be injected during construction time

- Once the service object has been supplied, the object can properly construct itself and continue on to do whatever job it has been invoked to do

What this means code wise for us .NET-ers is that we effectively need to supply registered services within a class' constructor, where the service container will recognize there's a dependency on said registered service in order for the dependent class to be properly constructed. If that's not a circular explanation, I don't know what is.

In our .NET Core applications, we deal with registered service container objects and classes on a regular basis -

ASP.NET Core Controllers, Entity Framework Core's DbContext

s, MediatR's IRequest object, and the list goes on. Thanks to the IoC container,

the details of how these objects are registered and requested at runtime are abstracted from us, allowing us to

effectively construct our registered classes with any number of other registered services of our choosing. There's

probably something I'm missing here, but I'll let the experts chime in and fill the gaps where necessary.

Service lifetimes

Alright, back to business. Like we mentioned, there are three service lifetimes we can access through the dependency injection extension namespace in transient, scoped, and singleton. The plain english explanation is as follows:

- transient - these services are constructed anew every single time they're request from the service container and

will never persist across registered containers (i.e.

ServiceCollections that have outlived the scope of one another) - scoped - services that are constructed once during the lifetime scope of a

ServiceCollectionand persist across service requests each time they're requested within the lifetime scope of a service container - singleton - services that are constructed only a single time during the lifetime of an application, and persistent across service container lifetime scopes

That seems like a lot of hoobla, so let's see service lifetimes in action to really try and make sense of all of this.

An example console application

Let's kick things off by creating a new console application. I'll be using Visual Studio for Mac to change things up a

bit, and I'll create a simple console application using the File > New Project. I'll name my

project DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes and let leave the rest of the defaults. Feel free to checkout

the source code anytime.

With our application bootstrapped, we should see just a single class file with Program.cs and nothing else. Now, we

could do this demonstration using an ASP.NET Core project, but we want to keep things simple without much project

overhead. Let's go ahead and add a package reference to the latest version of Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection

to our .csproj file using your preferred method. Again, I'll be using the Package Manager interface in VS for Mac, but

you're welcome to use the command line as well. Once we've a few got the package reference, let's go ahead and add

a Services folder to the root of our project.

With our Services folder in place, let's add three simple service classes that we'll each register with a different

lifetime. Go ahead and create three classes underneath Services: TransientService, ScopedService,

and SingletonService (creative, I know):

TransientService.cs

using System;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services

{

public class TransientService : IDisposable

{

public TransientService() =>

Console.WriteLine("Constructing a transient service...");

public void Dispose() =>

Console.WriteLine("Disposing of transient service...");

}

}

ScopedService.cs

using System;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services

{

public class ScopedService : IDisposable

{

public ScopedService() =>

Console.WriteLine("Constructing a scoped service...");

public void Dispose() =>

Console.WriteLine("Disposing of scoped service...");

}

}

SingletonService.cs

using System;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services

{

public class SingletonService : IDisposable

{

public SingletonService() =>

Console.WriteLine("Constructing a singleton service...");

public void Dispose() =>

Console.WriteLine("Disposing of singleton service...");

}

}

As we see, each of our services just informs us when they are constructed and disposed of, nothing else. Since we're

only exploring lifetimes, we don't need our services to do any sort of processing for the purposes of this post, so

we'll keep them nice and simple. We should point out that we're descending from an IDisposable parent in each

service - if we take a look at

the IServiceProvider

interface in the Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection library, we see that it also inherits from IDisposable.

When we create our service container and reference a scoped provider instance, the service scope in reference will

internally call Dispose at the end of its lifetime and subsequently Dispose of all applicable services within this

scope. We implement the Dispose method in each service simply for visibility to see this in action.

Let's go ahead and replace the current code in Program.cs with the following to kick things off and see what's going

on with all this service registration and request business:

Program.cs

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes

{

public class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Instantiate a service container and add each of our service lifetime types

var builder = new ServiceCollection();

builder.AddScoped<ScopedService>();

builder.AddTransient<TransientService>();

builder.AddSingleton<SingletonService>();

// Build our service container within the scope of our current program

using var serviceProvider = builder.BuildServiceProvider();

// Create a disposable instance of our service container and grab a couple of scoped references

Console.WriteLine("Building the first service container...\n");

using var firstScopedContainer = serviceProvider.CreateScope();

}

}

}

Initially, all we're doing is instantiating a service container instance with our builder reference to a

new ServiceCollection object, and adding each of our services as their respective lifetimes to the service container.

Typically, we'd use the .Add{LifetimeScope}<IMyService, MyService>() variant of the add method, but this will suffice

for our purposes - that's more a discussion of dependency inversion rather than injection and service lifetimes, maybe

I'll save that for a rainy day. With our services added, we'll construct a scoped instance of our service container with

the line using var serviceProvider = builder.BuildServiceProvider();, only valid until the end of our program, or

until we manually call Dispose. Once we have this scoped service provider reference, we'll grab another scoped

instance of the container to mimic an application request coming in to do some processing, requiring the IoC container

to pull services from.

Whew, there's quite a bit going on in just those few lines of code, but with that out of the way, let's do something a

bit more familiar to us - requesting scoped services. After we've created our firstScopedContainer reference, let's

grab a few scoped services from the container. Just below firstScopedContainer, let's add the following:

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes

{

public class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Previous service setup...

// Create a disposable instance of our service container and grab a couple of scoped references

Console.WriteLine("Building the first service container...\n");

using var firstScopedContainer = serviceProvider.CreateScope();

var scopedServiceOne = firstScopedContainer.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<ScopedService>();

var scopedServiceTwo = firstScopedContainer.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<ScopedService>();

// Validate that our scoped services are the same object reference, existing within the same service container scope lifetime

Debug.Assert(scopedServiceOne == scopedServiceTwo);

}

}

}

With a couple references to our scoped services, fire up this application and see what's going on. Since I'm using

Visual Studio for Mac, I'll go ahead and hit F5, but a simple dotnet run from the command line of your choice should

do the trick as well. Let's see what we get:

Building the first service container...

Constructing a scoped service...

Disposing of scoped service...

Notice how we only saw the constructor of IScopedService called once, as its only purpose was to inform us its

constructor was called. Recall that scoped services are constructed once per request, where our firstScopedContainer

is effectively playing the role of an application request to do some processing. Even though we requested

the ScopedService twice, our service container instantiated said service one time, and upon requesting the same

scoped service again with scopedServiceTwo, we got back the same reference to the previously

constructed ScopedService object. As our application lifecycle comes to an end, we see that the Dispose method of

our ScopedService was called as our program cleans up its resources.

If you're unfamiliar debug assertions (i.e. the line Debug.Assert(scopedServiceOne == scopedServiceTwo);), it's quite

a useful tool provided by the System.Diagnostics namespace. Anytime we place a Debug.Assert(bool condition) within

our code, our application will automatically break, similar to a hitting a breakpoint, when we run in debug mode and

our condition evaluates to false. Note that this has no effect when running in a release configuration. Here, we use

the assertion to check that our scoped service references are in fact the same object reference, as scoped services are

constructed only a single time per application request.

Alright, with our scoped services constructed, let's see what happens when we grab some references to our transient services. Just below our debug assertion for our scoped services, let's add the following:

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes

{

public class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Just below our Debug.Assert() line...

// Create our transient services are difference object references within the same service scope

var transientServiceOne = firstScopedContainer.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<TransientService>();

var transientServiceTwo = firstScopedContainer.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<TransientService>();

// Validate that our transient services are not the same object reference, newly created for each request from the container

Debug.Assert(transientServiceOne != transientServiceTwo);

}

}

}

With a couple of references to initialized to our TransientService retrieved from our service container, let's run our

application once more to see what's going on. Again, hitting F5 in Visual Studio:

Building the first service container...

Constructing a scoped service...

Constructing a transient service...

Constructing a transient service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of scoped service...

Okay, so we got a bit of different output this time. Notice that still we only get one instance constructed for

our ScopedService type, but now we get two constructed instances of our TransientService type. Recall that the

transient service lifetime will construct its registered service per request from the container, regardless of request

scope. In plain english, each time we request a transient service, we're getting a fresh, brand spanking new service

object. Again, we'll use a debug assertion to assert that our transient services are different object references just to

be sure. Once more, when our application lifecycle comes to an end, all the services are cleaned up, as we can see from

the three lines letting us know that each requested service had its Dispose method called.

With our transient services in place now, let's see what happens when we bring our singleton service into the mix. Just below the debug assertion for our transient services, let's add the following:

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes

{

public class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Just below our Debug.Assert() line...

// Create our singleton services are the same object reference within the same service scope

var singletonServiceOne = firstScopedContainer.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<SingletonService>();

var singletonServiceTwo = firstScopedContainer.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<SingletonService>();

// Validate that our singleton services are the same object reference, existing for the lifetime of the application

Debug.Assert(singletonServiceOne == singletonServiceTwo);

// Dispose of our current service container and create a new one

firstScopedContainer.Dispose();

}

}

}

Running our code now should produce the following output:

Building the first service container...

Constructing a scoped service...

Constructing a transient service...

Constructing a transient service...

Constructing a singleton service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of scoped service...

Disposing of singleton service...

Nothing has changed with our scoped and transient service constructions, or disposals. The only new lines we see now are

the construction and disposal of our singleton service. It might be tempting to infer that singleton services and scoped

services might act similarly, but that's not the case. Recall that singleton services are constructed once per

application lifetime. Our application lifetime only has one "request" coming in so far, and finishes its "processing"

once we hit the line firstScopedContainer.Dispose();. This is all fine and dandy, but what happens when we have

multiple request coming in?

Let's add another request facade in our application and see what happens we ask for services. Just below the debug assertion for our singleton service, let's add the following:

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes

{

public class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Just below our Debug.Assert() line...

// Create another scoped service container instance and grab a few more of our lifetime services for comparison

Console.WriteLine("\nBuilding our second service container...");

using var secondScopedContainer = serviceProvider.CreateScope();

// Create another scoped service instance and compare it's object reference to the previous scoped instances

Console.WriteLine("\nGrabbing a reference to another scoped service...");

var anotherScopedService = secondScopedContainer.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<ScopedService>();

Debug.Assert(anotherScopedService != scopedServiceOne && anotherScopedService != scopedServiceTwo);

}

}

}

Running our program now, we get the following:

Building the first service container...

Constructing a scoped service...

Constructing a transient service...

Constructing a transient service...

Constructing a singleton service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of scoped service...

Building our second service container...

Grabbing a reference to another scoped service...

Constructing a scoped service...

Disposing of scoped service...

Disposing of singleton service...

Can you spot the difference in output now? After our first service scope has been disposed, we clean up our references to our transient and scoped services, but our singleton service lives on. When we create a new request scope and grab another scoped service instance, our scoped service container creates another scoped service for us, as our scoped service lifetimes does not persist across application request scopes. Once our program ends, we do our usual cleaning up of our newly requested scoped services, but notice now that our singleton service is disposed of after our second application "request" comes in and our application's life comes to end (harsh). Let's see what happens when we add another transient service reference. Again, just below our last debug assertion:

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes

{

public class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Just below our Debug.Assert() line...

// Create another transient service instance and compare it's object reference to the previous transient instances

Console.WriteLine("\nGrabbing a reference to another transient service...");

var anotherTransientService = secondScopedContainer.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<TransientService>();

Debug.Assert(anotherTransientService != transientServiceOne && anotherTransientService != transientServiceTwo);

}

}

}

And once again, running this code we get:

Building the first service container...

Constructing a scoped service...

Constructing a transient service...

Constructing a transient service...

Constructing a singleton service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of scoped service...

Building our second service container...

Grabbing a reference to another scoped service...

Constructing a scoped service...

Grabbing a reference to another transient service...

Constructing a transient service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of scoped service...

Disposing of singleton service...

Focusing on the output after our second scoped application request, we see that as we request another transient service, our service container constructs yet another service instance for us, as transient services are instantiated each time they're requested regardless of request scope. Once again, all of our request services from the second request scope are disposed of as our application cleans up its resources. Lastly, let's add one more reference to our singleton service:

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes.Services;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace DependencyInjectionServiceLifetimes

{

public class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Just below our Debug.Assert() line...

// Create another singleton service instance and compare it's object reference to the previous singleton instances

Console.WriteLine("\nGrabbing a reference to another singleton service...");

var anotherSingletonService = secondScopedContainer.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<SingletonService>();

Debug.Assert(anotherSingletonService == singletonServiceOne && anotherSingletonService == singletonServiceTwo);

}

}

}

Once again running this code, we get:

Building the first service container...

Constructing a scoped service...

Constructing a transient service...

Constructing a transient service...

Constructing a singleton service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of scoped service...

Building our second service container...

Grabbing a reference to another scoped service...

Constructing a scoped service...

Grabbing a reference to another transient service...

Constructing a transient service...

Grabbing a reference to another singleton service...

Disposing of transient service...

Disposing of scoped service...

Disposing of singleton service...

Again focusing on the output after we create another request scope, we see that even across requests, when we reference a singleton service from our container, we get the same reference back from the first time it was constructed within the scope of our first request. Remember that singletons are created only once per application lifetime, so we don't see the call to the constructor once we request it once again from our second request scope. Nothing new with our resource cleanup either.

Wrapping up

Another day, another service lifetime explored. We've seen how different service lifetimes construct themselves at

request time and are cleaned up by their respective resource manager. When registering service lifetimes, we have to put

some thought into what kind of lifetime scope it should. Would you want a service that utilizes IDbConnection to be a

singleton? Probably not, as you might have a few angry customers on your hands. After today, I know I'll be a little

more conscious about the lifetimes I choose.

Until next time, amigos!