Welcome to buzzword bingo, a.k.a. how many resume keywords can we fit in one blog post before someone stops reading. If you're like me, you've comfortably relied on Entity Framework Core as your go-to ORM for .NET Core projects. Rightfully so, EF Core serves its purpose, and does its job very well. Primarily as a Java developer, I often daydream about having the ease, convenience, and configuration of EF Core in place of JPA (seriously, toss a few HQL queries in your code base and then tell me how much fun you're having).

I love EF Core for its tooling, ease of use, and deep integration with .NET Core. However, it's always nice to take a step back from the tools are seemingly default to and explore new horizons. It just so happens that the folks at StackOverflow, the site primarily responsible for my paychecks, developed another useful micro-ORM that we can use - and boy, does that baby purr. Checkout Dapper's GitHub page, in particular the benchmarks recoreded by the team. Dapper not only rivals the use case of ORMs like EF Core and NHibernate, it damn near beats them out of the water!

In this series, we'll explore building a simple CRUD web application built with ASP.NET Core, Dapper, and MediatR (to spice things up a bit). Before we get started, let's discuss the architecture of exactly what we'll be building. Far too often, I read how-to articles of X technology and how to accomplish Y task. For a simple CRUD application like we'll be building, and probably for most modern business software, shoving everything into one project solution will suffice.

We'll be building a simple CRUD API for our fictional brewery management software, Dappery. I always try to encourage clean architecture, so we'll be doing things a little differently. Let's go over our project structure:

- First, we'll implement a simple domain layer containing our persisted entities, data transfer objects, view models and resources, and most of our core domain business logic.

- Once our domain layer is in place, we'll slap a data access layer on top of it. This layer's sole responsibility is database interaction - no more, no less.

- Following the data layer, we'll add our core business layer project that acts as the middle-man between our web layer and our data access layer. We'll use MediatR and FluentValidator to do the heavy lifting in this layer.

- Once our core business logic layer is in place, we'll top things off with our API layer for the world to interact with. This layer will contain our ASP.NET Core project, with things like thin controllers, NO business logic (this is important, our API is the doorway to our application), and a simple Swagger doc for consumers to reference.

In this post, we'll get started with our domain layer. I should mention that we'll also be using .NET Core 3.0 with its new bells and whistles. Let's fire up a terminal (apologies, I'll be working exclusively on a Mac), and get started. If you're using Visual Studio, go ahead and initialize a new solution. In the terminal, let's start a new solution:

~$ mkdir Dappery && cd Dappery

~/Dappery$ dotnet new sln

Caveat: it's totally okay to fire up your favorite IDE (I'll be using Rider) and doing all this setup through the GUI.

This is just my preference for project setup. Next, let's go ahead and add some src and tests directories, and spin

up our domain layer project within the src directory:

~/Dappery$ mkdir src && mkdir tests

~/Dappery$ cd src && dotnet new classlib -n Dappery.Domain

Things to note are the fact that this is a classlib, which means this is a netstandard2.0 library that we can reuse

in any .NET project that leverages the standard. Now that we've got our project skeleton, let's go ahead and link it to

our solution:

~/Dappery/src$ dotnet sln ../Dappery.sln add Dappery.Domain/Dappery.Domain.csproj

Project `src/Dappery.Domain/Dappery.Domain.csproj` added to the solution.

With our solution linked to our domain project, let's go ahead and fire up our IDE with the project. As I mentioned

previously, I'll be using Rider. If your IDE hasn't already, I'd suggest adding the src and tests folders as project

folders, just to keep everything tidy. With our domain project skeleton in place, let's talk about what exactly we'll be

putting in this layer.

The Domain Layer

There's a popular architectural design pattern in software engineering

called Domain Driven Design, or DDD. To summarize, DDD takes the

approach that your application should be centered around your core domain model and business logic. In layman's terms,

what this means for us is that our domain layer project will house our beer and brewery entities and any special

business logic that pertains to these entities. This layer should not have ANY dependency on other layers; all this

layer knows, and cares about, is its entities and models. We'll also put our media types, or data transfer objects, in

this project as well to act as the middleman when moving data between layers. Let's create an Entities folder within

our Dapper.Domain project. We'll place two POCOs (plain old C# classes) that will act as our persisted database

entities, Beer.cs and Brewery.cs. To keep our code DRY,

we'll derive these classes from a TimeStampedEntity that will contain some common properies Beer and Brewery will

need.

TimeStampedEntity.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Entities

{

using System;

public class TimeStampedEntity

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public DateTime CreatedAt { get; set; }

public DateTime UpdatedAt { get; set; }

}

}

Beer.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Entities

{

public class Beer : TimeStampedEntity

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public BeerStyle BeerStyle { get; set; }

public Brewery Brewery { get; set; }

}

}

Brewery.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Entities

{

using System.Collections.Generic;

public class Brewery : TimeStampedEntity

{

public Brewery()

{

Beers = new List<Beer>();

}

public string Name { get; set; }

public Address Address { get; set; }

public ICollection<Beer> Beers { get; set; }

}

}

You'll notice I've put my using directives within my namespaces. This is purely preference, and has very little

difference than if I were to put them outside my

namespaces. Here's

a great discussion about the difference, for the curious. Also notice I've also created an Address class associated to

a Brewery and a BeerStyle enumeration so we can strongly type our families of beer. We've also initialized

our Beers list within our Brewery model - this is a great pattern to get into when working within the domain layer,

as consumers of our API should not have to worry about NullReferenceExceptions when interrogating logic based on a

collection from their API provider.

Address.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Entities

{

public class Address : TimeStampedEntity

{

public string StreetAddress { get; set; }

public string City { get; set; }

public string State { get; set; }

public int ZipCode { get; set; }

}

}

BeerStyle.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Entities

{

public enum BeerStyle

{

Lager,

Pilsner,

Amber,

PaleAle,

Ipa,

DoubleIpa,

TripleIpa,

Stout

}

}

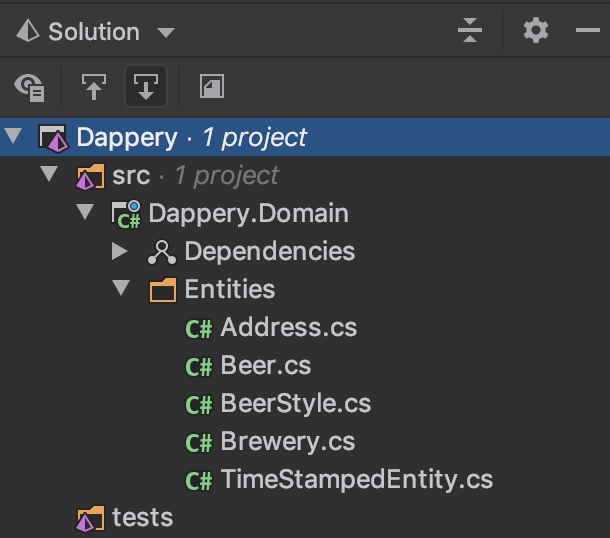

For the scope of this series, we'll keep things simple and stick with these properties for our entities. Our project should look a little something like this:

With our entities in place, let's go ahead add our DTOs. Before we do that, let's talk about what exactly we should be putting in these DTOs.

DTOs

For our implementation, we want our DTOs to reflect actions we can perform on our application. This a CRUD application,

but we're also going to

utilize Command and Query Responsibility Segregation,

or CQRS, to distinguish actions we'll be performing on our database - read only queries, and write commands. For our

simple application, it's tempting to have all-purpose DTOs for each CRUD operation. While this is a viable solution, I

would highly recommend against it. As our application grows, so do our needs for more complex queries and actions we

can perform on our database. Rather than trying to shove all that container logic into a few classes, we'll be

separating our DTOs by media type and action. Let's go ahead and add a Dtos folder, and within that folder, we'll add

separate folders for our different domains, Beer, and Brewery. and add our first create DTOs for a beer and a

brewery.

Brewery/CreateBreweryDto.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Dtos.Brewery

{

public class CreateBreweryDto

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public AddressDto Address { get; set; }

}

}

Beer/CreateBeerDto.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Dtos.Beer

{

using Entities;

public class CreateBeerDto

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public BeerStyle Style { get; set; }

}

}

Notice I've also added an AddressDto as an acceptable media type to the CreateBreweryDto class, so let's define that

as well at the root of the Dtos folder since this will be an all-purpose DTO since its properties do not change as we

do not directly CRUD with Address class.

AddressDto.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Dtos

{

public class AddressDto

{

public string StreetAddress { get; set; }

public string City { get; set; }

public string State { get; set; }

public int ZipCode { get; set; }

}

}

In our CreateBeerDto class, we're only exposing the name and beer style associated to a beer - why not a brewery? This

is where we'll define our first business rule:

Business Rule 1: A beer cannot be created with an associated brewery

What does this mean for our users? In order to add a beer to our database through our API, we'll add an endpoint associated with our breweries that will expose an add beer operation. This will simplify our API, as we will not need to do any association at creation time to the brewery for the beer to be added - we'll know exactly what brewery to add it to!

For our CreateBreweryDto class, we're exposing the name and the address of the brewery, NOT the list of beers. This

brings us to our second business rule:

Business Rule 2: A brewery cannot be created with beers on a request

While this may seem arbitrary, this rule will simplify our API, forcing users to first create a brewery, and

subsequentially add the beers to that brewery at their leisure. We'll see later why we're implementing this design, both

for simplicity for the developer and ease of use for our users. This brings up a good point - metadata. Let's add some

properies to our Brewery.cs entity to easily extract the number of beers a brewery has to offer. Let's add

a BeerCount property:

Brewery.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Entities

{

using System.Collections.Generic;

public class Brewery : TimeStampedEntity

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public Address Address { get; set; }

public ICollection<Beer> Beers { get; set; }

public int BeerCount => Beers.Count;

}

}

We've added a BeerCount delegate that will simply give us a count of all beers related to that entity whenever we

query for a specific brewery. With our create DTOs out of the way, let's go ahead and implement the rest of our CRUD

DTOs. For our reads, we'll create simple BeerDto.cs and BreweryDto.cs classes - no need to prefix these with an

operation as they will more, or less, be our default DTO when moving between layers:

BreweryDto.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Dtos.Brewery

{

using System.Collections.Generic;

using Entities;

public class BreweryDto

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public AddressDto Address { get; set; }

public IEnumerable<Beer> Beers { get; set; }

public int BeerCount { get; set; }

}

}

BeerDto.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Dtos.Beer

{

using Brewery;

using Entities;

public class BeerDto

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public BeerStyle Style { get; set; }

public BreweryDto Brewery { get; set; }

}

}

Nothing special here, the only difference is we'll be pulling out the ID for each beer and brewery, respectively. Note,

we're using IEnumerable<Beer> as our iterative type on our beers because this is just an immutable list, whereas we

used ICollection<Beer> in our entity due to the fact we will be modifying list over time.

With our reads out of the the way, let's go ahead and create UpdateBeerDto.cs and UpdateBreweryDto.cs classes:

UpdateBeerDto.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Dtos.Beer

{

public class UpdateBeerDto

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public AddressDto Address { get; set; }

}

}

UpdateBreweryDto.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Dtos.Brewery

{

using Entities;

public class UpdateBreweryDto

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public AddressDto Type { get; set; }

}

}

Again, nothing special here. We have an Id property on each DTO, as we'll need to know which beer, or brewery, to

update for the user on the request, and we're only allowing a few properties to change on our entities. Luckily for us,

for our delete operation, we'll be relying on the user to pass in an ID associated with the beer, or brewery, and that's

it. No need to include anything in the body, as long as we have the ID, we're good to. Let's take a minute to grab a

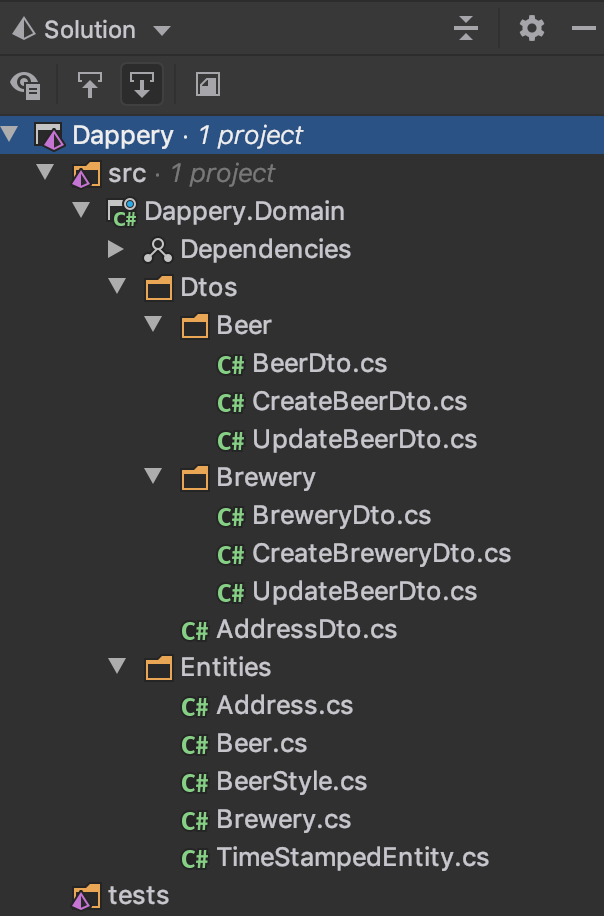

beer and take a look at where we're at so far. Our project structure should look more, or less, like this:

I promise we're almost done (sort of). That last knot for us to tie up is the media type we'll be presenting to our consumer. To be quite honest, this implementation is probably overkill for our use case, but a good exercise for us to build robust APIs. For our API, our entities and DTOs would suffice. However, in a real world enterprise setting, where our API interacts with tens of microservices all communicating with each other, a transfer data type that represents the media type and domain concern our API will provide to consumers is a good idea. Think of it as layers within our domain layer:

- Our entities represent the source of record stored within our database, that when extracted, are expected to modify and persist their state

- Our DTOs act as containers to transport that persisted data between layers (e.g. the domain layer and the data layer, and from the data layer to the API layer in the long run)

- Our API layer should not have any knowledge of our entities, as they contain audit properties (timestamps) and relations to other entities that should only be interacted with at lower layers

- Our resource types will represent the models/media types we will provide to our consumers, as our DTOs are more, or less, internal to our API

With the semantics out of the way, lets go ahead and create a Media folder and place a few resource types within that

folder:

Resource.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Media

{

public class Resource<T>

{

public T Self { get; set; }

}

}

Our general resource type that will serve as the template for all types our API will give to our consumers. As we build

our API, we'll continue to add metadata for our consumers so that they can make decisions about our responses we give

them without having to inspect the data we actually hand over. Next, let's create a ResourceList.cs class that will

serve as an iterable collection we hand over to our callers:

ResourceList.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Media

{

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

public class ResourceList<T>

{

public IEnumerable<T> Items { get; set; }

public int Count => Items.Count();

}

}

With a resource list in place, we have the building blocks to add our Beer and Brewery implementations of these

generic types:

BeerResource.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Media

{

using Dtos.Beer;

public class BeerResource : Resource<BeerDto>

{

}

}

BreweryResource.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Media

{

using Dtos.Brewery;

public class BreweryResource : Resource<BreweryDto>

{

}

}

BeerResourceList.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Media

{

using Dtos.Beer;

public class BeerResourceList : ResourceList<BeerDto>

{

}

}

BreweryResourceList.cs

namespace Dappery.Domain.Media

{

using Dtos.Brewery;

public class BreweryResourceList : ResourceList<BreweryDto>

{

}

}

While these classes may be simple and quite unecessary for now, we now have the ability to extend these resource types

based on the model implmentation as we wish. Our ResourceList type has a few built in properties (Items and Count)

for our consumers to always expect on a list type response, for example. With everything all said and done, our project

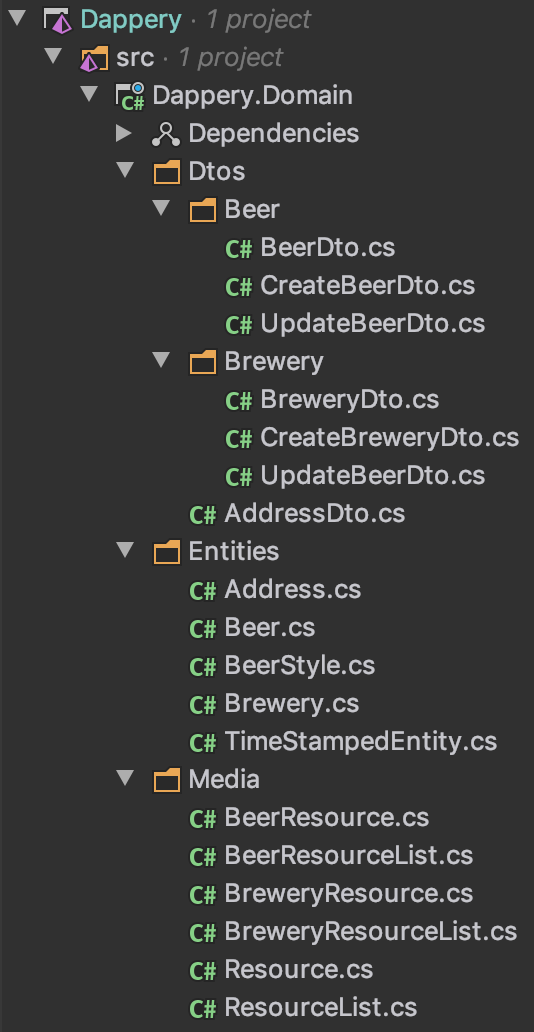

structure should look like the following:

For those following along, here's the repository of what we've done so far.

We can see the light at the end of the tunnel! A few lingering questions remain though, in particular with our tests

directory. We WILL be writing tests, but for our simple domain layer as of now, as there is really no logic in any of

the classes we've created so far, we're going to wait until we build the core functionality to start writing unit and

integration tests. For now, we'll stop here and continue with the meat and potatoes of our project in the next post in

the series, the data layer.

Crack open a cold, you deserve it.