Admittedly, or not, we've all worked on projects during our careers that took the above meme's approach of "just put it in the controller and we'll figure it out later". Unfortunately for some, this is a way of life due to project budget constraints, unrealistic product deadlines, and more senior developers refusing to change their ways because it "works." It's like how the old saying goes, you can't teach an old programmer to decouple independent concerns.

On a recent weekend getaway to the mountains, I did what I always do on long drives when my wife inevitably falls asleep in the car: put on episode of .NET Rocks! and let Carl, Richard, and their guests fascinate me with the latest in the .NET ecosystem. On this fateful day, the guest happened to be Steve Smith talking about his relatively new project - ApiEndpoints. I've listened to a lot of .NET Rocks! over the years, and needless to say, a problem that has always bothered me throughout my relatively young career as a developer seemed to finally have a simple solution.

The Problem

As previously mentioned, we've all most likely worked on a legacy project at some point during our careers that makes the company gobbles of money with no immediate plans of being sunsetted in place of a greenfield application, leaving other poor souls to maintain the mountain of tech debt accumulated over years of ignorance. While we could go down the rabbit hole of how a project eventually gets to this near unmaintainable state, I want to focus on a single area these projects, more often than not, have in common: the fat controller.

Bloated controllers

Not to be confused with the Thomas the Tank Engine character of the same name, fat controllers are a code smell, anti-pattern, etc. (pick your favorite buzzword) that boils down to a single issue at its root - controllers that are doing way too much, violating the SRP to the fullest extent of the law.

Controller bloat, in essence, is the product of compounding controller files with a plethora of action methods that, while related by their respective domain or managed resource, have no real dependence on one another. I'm not sure about you, but I don't think I've ever seen a controller action being called by another action within the same file. Sure, we might route resource requests at the API level to other methods with the same controller, but rarely is there a reason to directly call an action method explicitly from another. An unfortunate side effect of this phenomenon is a god class mentality developers take on, ignoring architectural boundaries, and injection of dependencies that service only a specific use case within said controller, ignored by 90% of the other actions.

What this eventually leads to (not in all cases, but a good majority), are controllers with thousands of lines of code containing an uncomfortable amount of business logic, constructors with an unnecessary amount of injected dependencies, and a regular trip to our local pharmacy for headache medication due to maintenance effort of these beasts.

ApiEndpoints to the rescue

Enter ApiEndpoints, a project started by Steve Smith with one goal in mind: decoupling from controller-based solutions by encouraging a package by feature architecture from within our API project layers.

What this means, in plain english, is a mindset change from the traditional MVC patterns we see in large web API

projects where there's most likely a Controllers folder that might contain tens of hundreds (yes, seriously)

controllers that act as the gateway into the lower level working parts of our application and act as the liaison

for client requests. Traditionally, this sort of architecture is akin to package by layer which we see in a grand

majority of projects within the enterprise, GitHub, your friend's sweet new app that's going to make them millions of

dollars.

What this boils down to, at the surface level, is an attempt to group related concerns and request work flows, i.e. how a request enters and trickles through the system interacting with our various application resources, within the same domain. What we're used to seeing might be similar to the following:

\Controllers

\Models

\Views

\Services

// ...and any number of layer-based components

Our controller directory might be broken down further:

\Controllers

HomeController.cs

\Orders

OrdersController.cs

OrderProcessingController.cs

\Products

ProductsController.cs

ProductInventoryController.cs

// ...again, any number of controllers nested within

Our Models, Views, and Services folders might very well contain the same, or very similar, structure. In this

example, we've created a package by layer architecture within our application - though everything exists in a single

DLL, these would be more often utilized and referenced as separate class libraries, JARs, etc.

What happens when a new business requirement comes in requiring a change, update, or addition to a specific feature? As you might have guessed, from our example we'll most likely be making changes in four separate places/layers of our application, though the feature falls under a single domain. As with everything in software, your preferred package methodology will always have payoffs, and the tried and true, handy dandy, all encompassing answer to the question of which ideology is best is simply... it depends.

While we could dedicate an entire post about putting things where they belong and the tradeoffs of different packaging

architectures, we're focusing on just the API layer of our applications, namely everything under the Controllers

folder. Our aim, with help from the ApiEndpoints library, will be to sort concerns within individual Feature folders.

Specific to the API layer, a.k.a. our controllers, as we want to decouple services, dependencies, and independent

processes from bloated, monolithic controllers. Imagine our orders controllers containing the following actions:

OrdersController.cs

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

using SomeAwesomeNamespace.Services.Orders;

namespace SomeAwesomeNamespace.Controllers.Orders

{

[ApiController]

[Route("[controller]")]

public class OrdersController : ControllerBase

{

private readonly ILogger<OrdersController> _logger;

private readonly OrderServiceOne _serviceOne;

private readonly OrderServiceTwo _serviceTwo;

private readonly OrderServiceThree _serviceThree;

public OrdersController(

ILogger<OrdersController> logger,

OrderServiceOne serviceOne,

OrderServiceTwo serviceTwo,

OrderServiceThree serviceThree)

{

_logger = logger;

_serviceOne = serviceOne

_serviceTwo = serviceTwo

_serviceThree = serviceThree

}

[HttpGet]

public ActionResult SomeActionThatUsesServiceOne()

{

// Do some processing requiring service one...

}

[HttpPost]

public ActionResult SomeActionThatUsesServiceTwo()

{

// Do some processing requiring service two...

}

[HttpPut]

public ActionResult SomeActionThatUsesServiceThree()

{

// Do some processing requiring service three...

}

// ...and any number of action methods to be utilized elsewhere

}

}

Our controller contains three service-based dependencies only utilized by a single method. Our controller is now coupled to three services, independent of one another, and consumed in only a third of its methods on a per service basis. While this might be a bit of a contrived example, it's easy to see how we might extrapolate this controller into a real world scenario, adding more services and methods that have nothing to do with one another, making it more difficult to change and modify this controller as it becomes more coupled to its injected dependencies. When the time comes to test this bad boy, it will inevitably become a mocking nightmare.

So... how can we improve upon the paved path the old guard has laid before us?

Endpoints as units of work

Continuing from our example above, let's think about what our API routing structure might look like:

/api/orders

/api/orders/process

/api/orders/:orderId

/api/orders/:orderId/products

/api/products

/api/products/:productId

/api/products/:productId/orders

// ...and any number of routes our application might service

From the above, we could argue that based on domain, those routes probably belong in two separate controllers,

product-based and order-based controllers. While that would suffice and get the job done for us, what about taking each

of the above routes as an individual unit of work? Not to be confused with

the design pattern

of the same name, our definition of a unit of work in this context represents a processing silo in charge of one thing,

and one thing only: /api/orders would be in charge of retrieving all outstanding/pending

orders, /api/products/:productId, would be in charge of retrieving products given a unique identifying

key, /api/orders/:orderId/products retrieves all the products on a particular order, etc. Each of these routes, while

related by domain, performs a very specific task unrelated to its sibling routes with a good chance that each requires

some sort of injected service that may, or may not, be utilized by the others.

While we could, again, dedicate an entire post to discuss API design semantics, let's break away from our conventional thinking and explore building an API without traditional controllers.

Individual endpoints with ApiEndpoints

As I'm sure the fine folks reading this article would love for me to continue aimlessly writing about orders and products for a fictional company, I'll shut up for now and finally get into some code. To start, let's create a new web API project using your preferred project bootstrapping method. I'll be using Visual Studio for Mac, so I'll go ahead and select a new ASP.NET Core Web Application project using the API template, since we won't be doing anything with views.

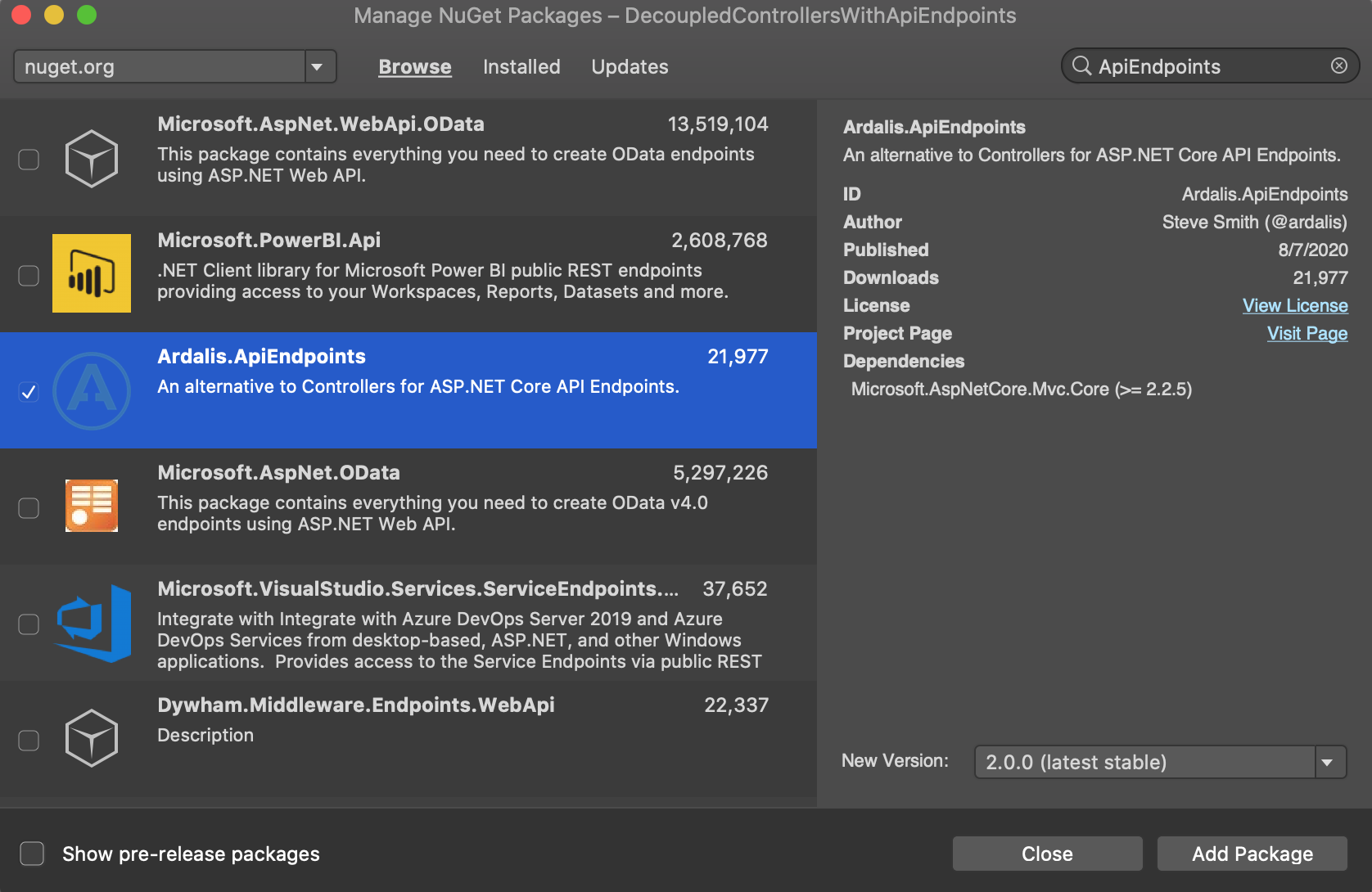

Once we've got a project ready to roll, let's open up our solution and do a bit of immediate refactoring. Let's start by

adding a package reference to Ardalis.ApiEndpoints:

Once our package has been added, let's create a Features folder at the root of our project, and immediately beneath

that, a Weather directory.

Let's go ahead and create two more directories beneath our Weather folder to house our concerns that have to deal with

everything related to weather in Models and Endpoints. By creating feature slices within our application, we can

group things by concern rather than by layer so that every feature request coming in from the business will be easily

contained within its corresponding domain. Let's start by offering up an endpoint to retrieve a weather forecast, akin

to the already existing method within the WeatherController.cs file underneath the Controllers folder. Go ahead and

add a new file underneath our Endpoints folder called GetWeatherForecasts.cs, where we'll place the action method's

code from the WeatherController's Get() method:

GetWeatherForecasts.cs

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using Ardalis.ApiEndpoints;

using DecoupledControllersWithApiEndpoints.Features.Beers;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

namespace DecoupledControllersWithApiEndpoints.Features.Weather.Endpoints

{

[Route(Routes.WeatherUri)]

public class GetWeatherForecast : BaseEndpoint<IEnumerable<WeatherForecast>>

{

private static readonly string[] Summaries = new[]

{

"Freezing", "Bracing", "Chilly", "Cool", "Mild", "Warm", "Balmy", "Hot", "Sweltering", "Scorching"

};

[HttpGet]

public override ActionResult<IEnumerable<WeatherForecast>> Handle()

{

var rng = new Random();

var forecasts = Enumerable.Range(1, 5).Select(index => new WeatherForecast

{

Date = DateTime.Now.AddDays(index),

TemperatureC = rng.Next(-20, 55),

Summary = Summaries[rng.Next(Summaries.Length)]

})

.ToArray();

return Ok(forecasts);

}

}

}

As the method definition for Handle() is the same as the Get() action method along with the other parts I've

directly copied over from the default WeatherController that the ASP.NET Core scaffold tools includes in its template,

let's focus on the unfamiliar parts of this file that ApiEndpoints brings to the table:

- We're still utilizing the

[Route]and[HttpGet]attributes available to our controllers thanks to theMicrosoft.AspNetCore.Mvcnamespace - We're inheriting from the

BaseEndpoint<TResponse>class that ApiEndpoints provides for us, signaling on application startup that this is, in fact, a controller in disguise and will be treated just like a regular old ASP.NET Core controller BaseEndpoint<TResponse>is an abstract class with a single method exposed for us to override inHandle()that anActionResult<TResponse>type, akin to action methods from within a controller- If we follow the inheritance chain of

BaseEndpoint, or any of its derivatives with higher order arity (thanks for the vocab upgrade in my personal arsenal, Jon Skeet) inBaseEndpoint<TResponse>orBaseEndpoint<TRequest, TResponse>, we see the base type ultimately pointing to ASP.NET Core'sControllerBasetype, solving the mystery as to why we have access to all the ASP.NET Core attributes and types in endpoints

We have a single named route thanks to the [Route(Routes.WeatherUri])] attribute, where I've defined Routes.cs at

the root of our Features folder below:

Features/Routes.cs

namespace DecoupledControllersWithApiEndpoints.Features.Beers

{

public static class Routes

{

public const string WeatherUri = "api/weather";

}

}

While most likely unnecessary for our small demo application, I find it helpful to have a single place containing our API routes for reference in other parts of our apps, should we need them. We'll add to this a bit later, but for now, this should suffice.

Let's spin up our application now using F5, or hitting a dotnet run in the terminal, and using Postman (or your

favorite web request utility), let's send a request to https://localhost:5001/api/weather and examine the response:

[

{

"date": "2020-09-23T12:52:27.408507-07:00",

"temperatureC": 6,

"temperatureF": 42,

"summary": "Mild"

},

{

"date": "2020-09-24T12:52:27.408951-07:00",

"temperatureC": -19,

"temperatureF": -2,

"summary": "Freezing"

},

// ...and several other random forecasts

]

Thanks to the rng we've built into our forecast generator, your response will look a bit different than mine, but

let's not gloss over the fact that we've just performed a complete request/response cycle within our API without using a

controller!